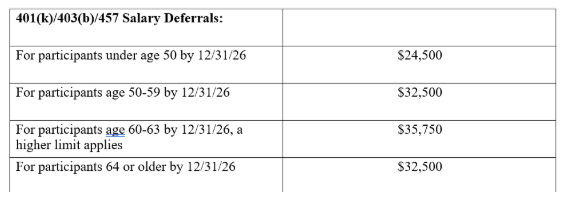

A relatively quiet, but crucial shift has been taking place in bond markets recently, with the steepening of the U.S. Treasury yield curve. After spending much of the past three years inverted or flat, the gap between short- and long-term interest rates has begun to widen again, which is a development investors should generally view as constructive for future economic growth.1

The chart below expresses the yield curve by subtracting short-term Treasury bond yields (3-month) from the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond yield. When the line dips below zero, that means the yield curve is inverted (short-term yields are higher than long-term yields). As readers can see, the line is finally crawling back up into positive territory.

3-month / 10-year U.S. Treasury Bond Yield Curve

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis 2

Part of the shift reflects changing expectations around Federal Reserve policy, including the nomination of Kevin Warsh as the next Fed Chair. Markets appear to be interpreting his nomination as a signal that short-term rates could eventually move lower, while long-term rates will reflect supply, demand, and inflation expectations more freely. The view on long rates is based on the fact that Warsh has been vocal over the years about shrinking the Fed’s balance sheet and pulling back from heavy bond-market intervention.

This combination, lower short-term rates and less ‘yield manipulation’ on the long end, naturally points toward a steeper yield curve.

From an economic perspective, a positively sloped yield curve tends to factor as a tailwind for growth, since it supports lending activity. Banks borrow short and lend long, so a wider spread between short-term funding costs and longer-term lending rates improves incentives to extend credit. If businesses can access capital more easily, that’s constructive for investment and growth.

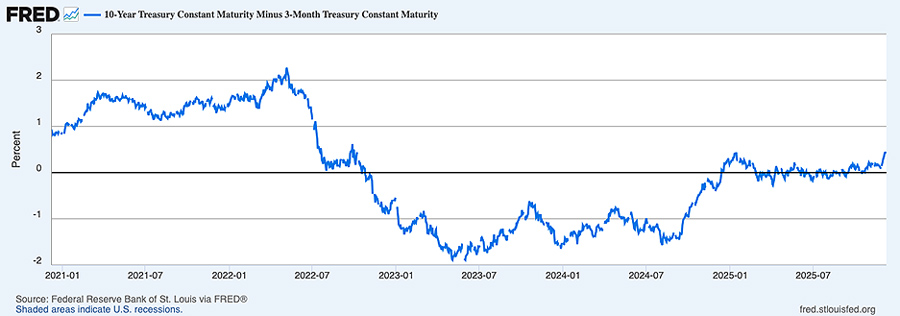

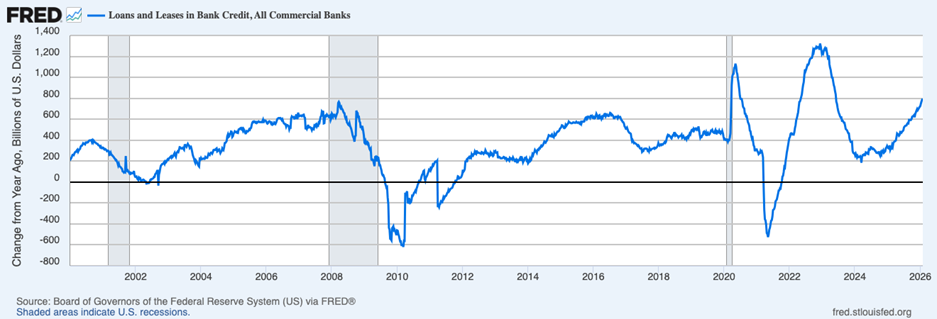

What’s interesting is that the opposite has not necessarily been true over the past few years. Even when the yield curve was inverted for the past two-plus years, bank lending didn’t stall. Total loan growth began in 2025 running at roughly a 2.7% year-over-year pace. By late November, it had accelerated to about 5.4% year over year. That is a meaningful improvement, especially considering rates were largely unchanged for much of the year and liquidity conditions were, by conventional standards, tightening rather than easing. As seen on the chart below, showing the year-over-year change in loans and leases in bank credit (in billions of U.S. dollars), credit has been flowing solidly since 2022.

Bank Lending (Year-over-Year Change in Billions of U.S. Dollars)

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis 3

If lending strengthened in 2025 despite relatively tight policy conditions and a flat yield curve, it suggests the economy was already standing on a fairly solid footing. The read here for investors is that looking ahead, a steepening curve is a positive signal, but not because it suddenly “unlocks” growth. Rather, I see the steepening yield curve as reinforcing a trend that was already in place, which reflects normalization. And that’s a good thing, in my view.

Bottom Line for Investors

The yield curve steepening is a constructive development, and it fits with a broader picture of an economy that has generally been healthier than appreciated. Equally important, the past two years showed that growth and lending will not always grind to a halt simply because the curve is inverted, reminding us that many other forces are at work.

But there’s another takeaway here for investors: just as the inverted yield curve for much of 2023 did not signal an imminent recession, a steepening yield curve in 2026 should not necessarily be viewed as a critical turning point for big growth ahead. We’re expecting growth to be solid this year, to be sure. But we expected that outcome even with a flat yield curve, underscoring the fact that lending, spending, and growth have been strong even without a traditionally steep yield curve. In that sense, the recent steepening looks less like a prerequisite for growth and more like an added tailwind to an economy that was already in good shape.

1 Wall Street Journal. January 31, 2026. https://advisor.zacksim.com/e/376582/i1WiljnrifkKiDv64j154vmpAA3D3D/5v4q6k/1462235389/h/L8P_TOFJ4WYshjSJYlqvePaYN-TpiLeuioNeejw7qRw

2 Fred Economic Data. February 10, 2026. https://advisor.zacksim.com/e/376582/series-T10Y3M/5v4q6n/1462235389/h/L8P_TOFJ4WYshjSJYlqvePaYN-TpiLeuioNeejw7qRw

3 Fred Economic Data. February 6, 2026. https://advisor.zacksim.com/e/376582/series-TOTLL/5v4q6r/1462235389/h/L8P_TOFJ4WYshjSJYlqvePaYN-TpiLeuioNeejw7qRw

DISCLOSURE

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Inherent in any investment is the potential for loss.

Zacks Investment Management, Inc. is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Zacks Investment Research. Zacks Investment Management is an independent Registered Investment Advisory firm and acts as an investment manager for individuals and institutions. Zacks Investment Research is a provider of earnings data and other financial data to institutions and to individuals.

This material is being provided for informational purposes only and nothing herein constitutes investment, legal, accounting or tax advice, or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a security. Do not act or rely upon the information and advice given in this publication without seeking the services of competent and professional legal, tax, or accounting counsel. Publication and distribution of this article is not intended to create, and the information contained herein does not constitute, an attorney-client relationship. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment or strategy is suitable for a particular investor. It should not be assumed that any investments in securities, companies, sectors or markets identified and described were or will be profitable. All information is current as of the date of herein and is subject to change without notice. Any views or opinions expressed may not reflect those of the firm as a whole.

Any projections, targets, or estimates in this report are forward looking statements and are based on the firm’s research, analysis, and assumptions. Due to rapidly changing market conditions and the complexity of investment decisions, supplemental information and other sources may be required to make informed investment decisions based on your individual investment objectives and suitability specifications. All expressions of opinions are subject to change without notice. Clients should seek financial advice regarding the appropriateness of investing in any security or investment strategy discussed in this presentation.

Certain economic and market information contained herein has been obtained from published sources prepared by other parties. Zacks Investment Management does not assume any responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of such information. Further, no third party has assumed responsibility for independently verifying the information contained herein and accordingly no such persons make any representations with respect to the accuracy, completeness or reasonableness of the information provided herein. Unless otherwise indicated, market analysis and conclusions are based upon opinions or assumptions that Zacks Investment Management considers to be reasonable. Any investment inherently involves a high degree of risk, beyond any specific risks discussed herein.

The S&P 500 Index is a well-known, unmanaged index of the prices of 500 large-company common stocks, mainly blue-chip stocks, selected by Standard & Poor’s. The S&P 500 Index assumes reinvestment of dividends but does not reflect advisory fees. The volatility of the benchmark may be materially different from the individual performance obtained by a specific investor. An investor cannot invest directly in an index.

The Russell 1000 Growth Index is a well-known, unmanaged index of the prices of 1000 large-company growth common stocks selected by Russell. The Russell 1000 Growth Index assumes reinvestment of dividends but does not reflect advisory fees. An investor cannot invest directly in an index. The volatility of the benchmark may be materially different from the individual performance obtained by a specific investor.

Nasdaq Composite Index is the market capitalization-weighted index of over 3,300 common equities listed on the Nasdaq stock exchange. The types of securities in the index include American depositary receipts, common stocks, real estate investment trusts (REITs) and tracking stocks, as well as limited partnership interests. The index includes all Nasdaq-listed stocks that are not derivatives, preferred shares, funds, exchange-traded funds (ETFs) or debenture securities. An investor cannot invest directly in an index. The volatility of the benchmark may be materially different from the individual performance obtained by a specific investor.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average measures the daily stock market movements of 30 U.S. publicly-traded companies listed on the NASDAQ or the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE). The 30 publicly-owned companies are considered leaders in the United States economy. An investor cannot directly invest in an index. The volatility of the benchmark may be materially different from the individual performance obtained by a specific investor.

The Bloomberg Global Aggregate Index is a flagship measure of global investment grade debt from twenty-four local currency markets. This multi-currency benchmark includes treasury, government-related, corporate and securitized fixed-rate bonds from both developed and emerging markets issuers. An investor cannot invest directly in an index. The volatility of the benchmark may be materially different from the individual performance obtained by a specific investor.

The ICE Exchange-Listed Fixed & Adjustable Rate Preferred Securities Index is a modified market capitalization weighted index composed of preferred stock and securities that are functionally equivalent to preferred stock including, but not limited to, depositary preferred securities, perpetual subordinated debt and certain securities issued by banks and other financial institutions that are eligible for capital treatment with respect to such instruments akin to that received for issuance of straight preferred stock. An investor cannot invest directly in an index. The volatility of the benchmark may be materially different from the individual performance obtained by a specific investor.

The MSCI ACWI ex U.S. Index captures large and mid-cap representation across 22 of 23 Developed Markets (DM) countries (excluding the United States) and 24 Emerging Markets (EM) countries. The index covers approximately 85% of the global equity opportunity set outside the U.S. An investor cannot invest directly in an index. The volatility of the benchmark may be materially different from the individual performance obtained by a specific investor.

The Russell 2000 Index is a well-known, unmanaged index of the prices of 2000 small-cap company common stocks, selected by Russell. The Russell 2000 Index assumes reinvestment of dividends but does not reflect advisory fees. An investor cannot invest directly in an index. The volatility of the benchmark may be materially different from the individual performance obtained by a specific investor.

The S&P Mid Cap 400 provides investors with a benchmark for mid-sized companies. The index, which is distinct from the large-cap S&P 500, is designed to measure the performance of 400 mid-sized companies, reflecting the distinctive risk and return characteristics of this market segment.

The S&P 500 Pure Value index is a style-concentrated index designed to track the performance of stocks that exhibit the strongest value characteristics by using a style-attractiveness-weighting scheme. An investor cannot directly invest in an index. The volatility of the benchmark may be materially different from the individual performance obtained by a specific investor.